The Case for Affirmative Action for Conservatives in Academia

A surprisingly cogent set of arguments

One time, in graduate school, I was talking to one of my PhD committee members when he said something that I found slightly outrageous. Not morally outrageous or anything — we were talking about some long-since-forgotten bit of philosophical esoterica — but nonetheless a claim that I found to be extremely implausible. “You don’t actually believe that, do you?” I challenged him. “Well,” he hesitated, “I’ve defended it in print.”

I’ve always loved that answer. While this may not have been his intent, I took away from the exchange the idea that the standards for belief and the standards for defending something in print are different. You should believe something if the evidence supports it, and it seems highly likely to be true. But it takes something different to defend something in print. You should defend something in print if there are cogent arguments in favor of it, and the strength of those arguments hasn’t been sufficiently appreciated. If something is worth taking seriously, but isn’t currently being taken seriously, it’s worth defending in print, even if you’re not sure you really believe it.

So let me defend affirmative action for conservatives in academia in print.

The question of affirmative action for conservatives in academia became a hot topic of conversation for a few days when Donald Trump threatened Harvard with severe consequences unless it gave in to a list of demands that went well beyond the demands that were made of Columbia a few weeks previously. One of those extra demands was a demand that Harvard engage in affirmative action favoring conservatives. This caused a massive uproar. Among liberals, this was lambasted as an assault on academic freedom, which it was. But even conservatives were largely opposed. I mean, the Trump cult loved it, but they love anything Trump does, so they can be safely ignored. But conservative troll-cum-intellectual Richard Hanania took to the Economist to make the case that affirmative action is always bad and merit in hiring is good, and that didn’t change just because Trump wanted it turned to conservatives’ favor. Most conservatives that I follow on social media seemed to agree with this assessment.

My own reaction was more conflicted. I had just argued that academia could not survive Republicans holding political power unless the institution was remade to be something that Republicans could support, however grudgingly. Part of that remaking, I argued, would have to involve affirmative action for conservatives. That was not really an argument for affirmative action, but rather a descriptive analysis of the dilemma facing academia: the choice is to implement affirmative action or face draconian funding cuts. I left it to the reader to decide which of those alternatives was more unpalatable; the point was just that that is the choice academia faces. My mood soured further on the topic once Trump started making these demands explicit. The choice remained the same, but the bitter pill of reform now came served with a side of even more bitter cowardice and capitulation to petulant authoritarianism. Resistance and financial ruin are all but assured.

But these political conflicts are largely a distraction from a genuine ethical question of whether affirmative action for conservatives is justified. Trump is pushing Harvard to implement the policy out of bitter, foolish vindictiveness, and Harvard is righteously resisting. But if none of that were happening, would it be good for academic institutions to implement affirmative action? I think there’s a strong case to be made that it would. My argument, in short, is that the case for modest forms of affirmative action are stronger than conservatives realize. And the rationale that supports modest forms of affirmative action absolutely obtains with regards to the situation of conservatives in academia (although liberals are largely in denial about this).

Let’s begin by saying what I mean by “modest affirmative action” and by examining what conservatives get wrong in their arguments for merit and against affirmative action. By “modest” affirmative action, I mean affirmative action as a sort of tie-breaker. Once all applications are in and the applicants are ranked according to merit, if there is a tie at the top, consideration should be given to other factors. This approach is opposed to more radical forms of affirmative action involving quotas, or where considerations like race or gender (or political affiliation) are used as a “first cut” to narrow the pool of applicants to only those from a targeted demographic. Affirmative action is, instead, a last cut.

I would also insist on rather stringent criteria for what it takes for two applicants to count as “tied,” such that affirmative action criteria might be brought to bear to break the tie. I’ve heard fellow philosophers argue that really the only criterion that matters when it comes to applying for a philosophy job is having a PhD, and so every applicant in the pool (apart from the one or two cranks who always end up applying) is effectively tied with respect to qualification. That being the case, we can make selections more or less entirely on the basis of demographic characteristics, secure that merit has been adequately taken into account. I reject that idea. When it comes to hiring for a research position, for instance, the quantity and quality of publications that an applicant has produced is clearly relevant. Someone with a dozen publications in top journals is more qualified than someone with no publications at all. This is obvious.

And yet things are rarely so cut and dried in actual hiring decisions. Sometimes there is one candidate who is a clear stand-out, with substantially more publications in substantially better journals than any other applicant. But often that’s not the case. Often, there are two or more candidates who are very strong, but in ways that it’s hard to meaningfully compare. One applicant has three publications, one in a top 5 journal, the other two in top 20 journals. Another applicant has six publications, 2 in top 20 journals, 4 in more niche journals, and none in the top 5. A third has only one publication, but it’s in Philosophical Review, the consensus best journal in the field. Which applicant has the strongest publication record? You could make a case for any of them. And that’s assuming we’re just looking at publication records. There’s another candidate in the pool whose publications are clearly (but marginally) less impressive, yet her teaching portfolio is outstanding. Teaching is a very important part of the job for almost all academic positions! And another candidate in the pool who is an accomplished conference organizer with a strong record of success in obtaining grants. Departments need people like that in order to thrive in the bureaucratic culture of contemporary academia. Which of these five candidates is the most qualified? Who comes out on top in terms of merit?

Decisions must be made, and so they are made. Hiring committees are a mess of squabbling (often congenial, but not always) about exactly what weights to place on each of these criteria. There will be the one person who’s really impressed by the Phil Review pub, the one who insists that we’re teachers first and foremost and that this is the most important thing to take into account (assuming that the publication record is strong enough to indicate a good candidate for tenure), and on and on. So it goes, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But to say that all of this squabbling is besides the point, for what really matters is who has the most merit, would be patently ridiculous. The squabbling results because each candidate has a plausible claim to being the most meriting. Given that each candidate has a plausible claim, what’s wrong with making the decision to hire the first black woman the department has ever employed? The objection is that this would put decisive weight on what is essentially an arbitrary factor. But that objection overlooks the fact that, in many cases, any decision will amount to putting decisive weight on what is essentially an arbitrary factor. If some further social good can result from doing so, then, honestly, that just sounds great. Let’s do that.

And all of this applies to the question of affirmative action for conservatives. If there is a genuine tie with respect to merit, what’s wrong with ensuring that there is conservative representation on the faculty? It’s no worse of an arbitrary factor than any other. And if some further social good can result from doing so, then let’s do that.

This just raises the question of whether some social good would come from making an effort to hire conservatives. And here it seems the answer is clearly yes.

Let us set aside the purely pragmatic case for affirmative action for conservatives that I referenced earlier. There are two standard justifications for affirmative action. One is that diversity is in the interest of institutions, and affirmative action promotes diversity. The second is that affirmative action is an appropriate remedy for past (and perhaps ongoing) discrimination. Both of these justifications clearly apply in the case of affirmative action for conservatives.

Let’s take the diversity issue first. This point has been made so many times over the last decade or so that I feel kind of silly trotting out the old talking points, but these arguments are no worse for the wear. Intellectual diversity is healthy in any institution, but particularly in an academic institution. A university where people come from every country of the world, with every conceivable skin tone and sexuality proudly represented, and where everyone thinks exactly the same thing is not a healthy academic institution.

Progress comes from disagreement. If you’re wrong, you need someone who disagrees with you to correct you. “Hmm, maybe I’m wrong about this” is just not the sort of thought that will occur to anyone who is surrounded by a chorus of people agreeing with you all day. And even if the thought does occur to you, the chorus of agreement will discourage you from pursuing the thought further, particularly if there are social consequences to voicing that disagreement. And even if you’re right, there’s value in holding onto your beliefs as a living truth rather than a dead dogma. Maintaining a living truth requires deep understanding, and it is deep understanding, rather than superficial correctness, that is the key to further discovery.

These points are all so obvious that it’s almost surprising that they’re not universally accepted. That these are controversial points at all becomes intelligible once you realize that if intellectual diversity is important, then that suggests that some sort of affirmative action for conservatives might be appropriate. And the idea of affirmative action for conservatives is seen as so laughably misguided that valuing “intellectual diversity” (always put in scare quotes) is taken to be equally misguided. My friends, it is time to seriously consider that we run the argument in the opposite direction and take some serious steps towards remedying academia’s political monoculture.

This point has been debated over the last few days after an OpEd by philosopher Jennifer Morton in the NYT which has elicited substantial controversy. I don’t want to engage directly with Morton here, since I’ve seen many others do so (this piece sums up my thoughts pretty nicely). But the main objection I’ve seen to intellectual diversity in the wake of the controversy is that we, as an academic community, have already considered conservatism and rejected it as being wrong, and part of the whole idea of an academic discipline is that we reject wrong ideas once we’ve sufficiently established them to be wrong. Here’s Brian Leiter:

Diversity, including viewpoint diversity, is not an academic value. …[V]iewpoint diversity is irrelevant in serious academic disciplines; in less serious ones, it may be relevant, but there is no way to impose it without violating core academic freedom. Academic disciplines presupposes the unequal worth of different viewpoints, and the job of scholars is to assess those viewpoints, and discount the unworthy ones.1

There is a good point here. We no longer teach phlogiston in chemistry class, nor flat earth in astronomy or geology. Our understanding of the world progresses in large part by discarding things that we have found not to work. The idea that intellectual diversity should require us to teach or engage with flat earth theory is laughable. Might we say the same thing about conservative thought?

We might not. Let’s begin by disentangling, to the extent possible, empirical claims about the way the world is from moral claims that tell us how we should respond to the way the world is. When it comes to empirical claims, I hesitate to call any empirical claim “conservative” or “liberal.” The relevant distinction is between empirical claims that are true and those that are false. Truth and falsity are often hard to discern, but we have our methods for sorting the one from the other, those methods seem to work pretty well, and we should apply them impartially. Now there are some claims that are false and unsupported by evidence and which tend to be believed disproportionately by conservatives nonetheless. Young earth creationism, for one. I’m not saying that we should be inviting young earth creationists into the academy, at least not as geologists or historians. Of course, this point cuts both ways. Homeopathy is a bizarre empirical system of beliefs that is left-coded, and it has no place in medical schools. This is as it should be.

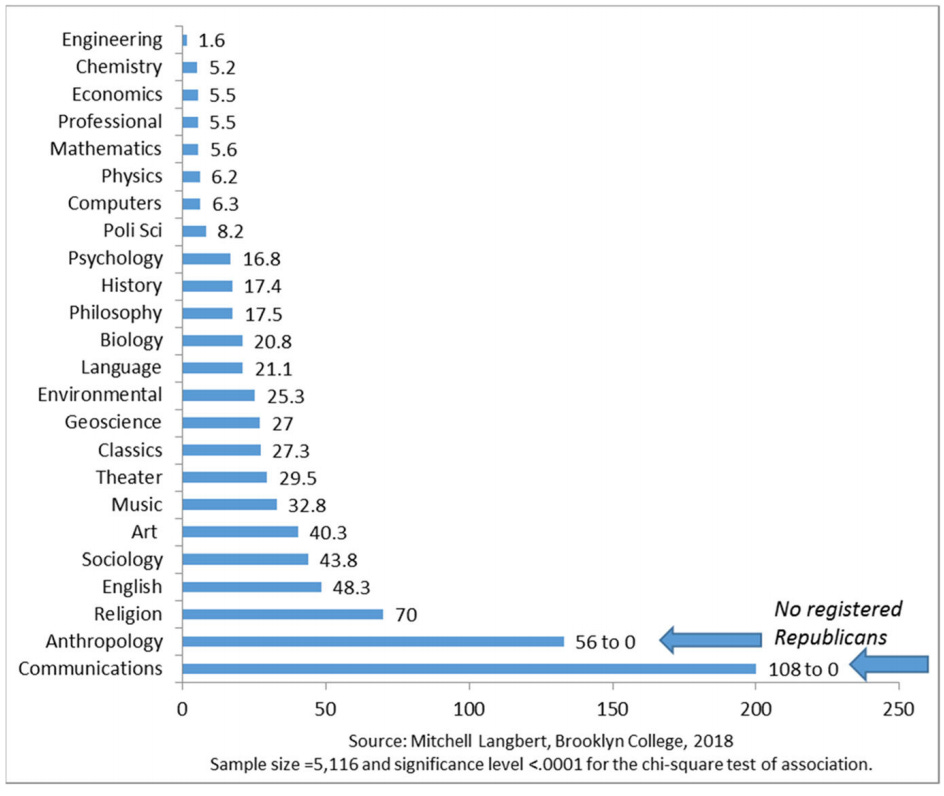

But moral beliefs are a different story. The sharpest controversies over conservative representation concern the inclusion of people with right-of-center beliefs about moral and political questions. These controversies are most pronounced when those questions concern race and gender, but these same controversies arise around every other moral and political issue - war, faith, political economy, liberty, equality, and on and on. For each of these issues, it’s not difficult to identify what would count as “conservative values” vs “liberal values.” And the academy just doesn’t have many people with conservative values. This matters the most when it comes to subject matters that either touch on moral issues or are themselves fundamentally moral or political disciplines. In most cases, it doesn’t much matter what a chemist’s attitudes towards the morality of war and peace are. But it is precisely in the disciplines that are moral or morality-adjacent that the bias against conservatives is most pronounced:

STATISTICAL bias, that is. I’m not talking about deliberate discrimination (yet). For now, our focus is on the question of whether or not it is sensible to discriminate against conservatives because we have determined that their beliefs are just wrong. Regarding moral beliefs, then, the claim would have to be that we, as an academic community, have come to the conclusion that conservative moral beliefs are just wrong, and so we are justified in rejecting conservatives in moral disciplines, just as we are justified in rejecting young earth creationists from the geology department.

This is a pretty incredible argument, since it presupposes both (A) that there are objective moral facts, and (B) that we can know those moral facts with something like the same degree of rational certainty that we have that young earth creationism is false. Are (A) and (B) true? Well, I certainly don’t think so. When I’m writing papers for publication in academic journals and not just tinkering on this here blog, my primary project is to argue that (A) and (B) are false. (Check out my book with Spencer Case on the matter!) So fully making the case that (A) and (B) are mistaken is a task that falls far outside the scope of this one blog post that’s already running far overlong. For now, I’ll content myself with the following three points: First, it’s hard to say what even could count as evidence for any moral claim. Most moral philosophers end up endorsing some version of “intuition” at one point or another, which is precisely as dubious as it sounds. Second, (A) and (B) as metaethical claims are themselves extremely controversial, and so it would be remarkable if a whole discriminatory hiring apparatus was based on them. Third, the idea that there are objective moral facts is widely rejected by the very people in the humanities who are so keen to discriminate against conservatives. When Brian Leiter isn’t arguing that it’s fine to discriminate against conservatives for having bad moral beliefs on his blog, he’s writing academic papers where he argues against moral realism on Nietzschean grounds.

Now, this isn’t necessarily inconsistent. Moral anti-realists don’t generally eschew first-order morality. They just understand their moral commitments as nothing more than their own personal attitudes. I’ve argued that this is consistent and sensible in my academic work. But that puts the idea that conservative values have been “discounted” as “unworthy” (to use Leiter’s words) in a different light. The argument, it appears, is not that we know that conservative moral beliefs are false. Rather, we as an academic community have just gotten together and decided that we don’t take conservative values seriously, and so, as a result, we’re happy to actively discriminate against conservatives in hiring. They’re not wrong, in any objective sense. We have just decided that we don’t want to have to deal with them.

This brings us to the final question: Do academics discriminate against conservatives? Uh, yes. Obviously. First piece of evidence: that graph above. 5.5:1 ratios of liberal to conservative in the hard(er) sciences, 20:1 in the soft sciences and the hard(er) humanities, 40:1 or worse in the arts and critical disciplines. That doesn’t happen by accident. Second, direct evidence:

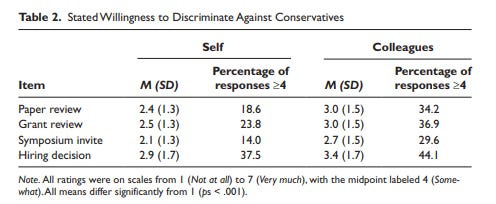

That chart is from a 2012 study by Inbar and Lammers.2 That’s 2012, before Trump, before the “Great Awokening.” Things have not improved. For those of you who go a bit cross-eyed when asked to read charts and tables (my sympathies!), this says that, for hiring decisions, most academics rated themselves at least somewhat likely to discriminate against conservatives, with 37.5% say that they themselves would be more likely than not to discriminate against conservatives, and 44.1% saying that of their colleagues.

Now you might not think that’s so bad. “Less than 50%…” But think about how hiring committees actually work, as I outlined above. There’s a debate over candidates, and a consensus needs to be reached. If the decision has to be unanimous, then a 40% chance of having a committee member biased against conservatives means that any committee of any decent size will have at least one biased member on it. (And then the recommendations of the committee go to the department as a whole, which can question the decision.) And even if unanimity isn’t required - as it usually isn’t, else no one would ever get hired - the existence of faculty members who are vocally opposed to hiring a conservative will count strongly against offering the job to the conservative for the rest of the committee. Because it is obvious that hiring the conservative will introduce a source of conflict into your nice, collegial department. Some people will go out of their way to make the conservative feel unwelcome; and even if that’s not what you will do, will you defend them? Then you’re on their side, battle lines are getting drawn, people stop talking to one another at department colloquia, and who really wants all of that? 40% of faculty being willing to discriminate against conservatives in hiring decisions translates into a much, much higher chance that no conservative will ever be hired.

And a third piece of evidence that academics discriminate against conservatives: In response to the recent controversy over intellectual diversity, one of the main lines of argument against intellectual diversity has been “But it’s good to discriminate against conservatives, because they’re wrong” (as we just saw above).

The common response to this worry is that conservatives are just less worthy of being hired. This response comes in three varieties. The first is the bald-faced “discrimination is good actually, provided it’s against conservatives, because I don’t like conservatives” line that we looked at a few paragraphs ago. Suffice it to say that I think this is a pretty loathsome attitude, and that one of the best justifications of affirmative action is that it can push back on bigoted nonsense like this. The second is the idea that conservatives are inherently less intelligent than liberals and that they are therefore less likely to even pursue careers as academics. I take this to be little better than the first variety. “There’s just not that many of them in academia because they’re intrinsically stupid” is the sort of line that appears easily in the mouths of bigots and segregationists of all stripes. “Of course they’re dumb, they’re conservative!” That plays well as a laugh line, but it’s got little basis in research on intelligence. It also seems to assume that in order for one to have the best values, one must simply be intelligent. Liberals are right and conservatives are wrong - just think about it, and that will become clear! Again, this assumes a certain perspective on moral epistemology that is highly controversial, to put it lightly, and most likely to be condemned in the abstract by those who are most eager to put it into practice.

It is true that conservatives are less likely to pursue careers as academics, but the better explanation for that is that every conservative with academic inclinations knows that the academic job market is highly competitive and that they are likely to be actively discriminated against on that job market. Why take the years to get a PhD when it will all go to waste? It’s true that universities can’t just turn around and fill up their departments with conservatives because there is a massive pipeline problem in conservative academia. But the traditional solution to pipeline problems that result from past (and potentially ongoing) discrimination is… affirmative action.

The third variety of “conservatives are less worthy to be hired” is the most defensible, since it comes from simple examination of CVs. Conservatives have fewer publications, and thus are less likely to be hired on the strength of their research. Accordingly, something more than the moderate affirmative action that I talked about at the top of this post would be required to increase conservative representation. This is often true (although there are exceptions).

There are two points to make in response here. First is that this CV deficit is itself often the result of discrimination. In the Inbar and Lammers study, 34% of academics said that their colleagues would be more likely than not to discriminate against a conservative paper if they reviewed it for a journal. This is very likely to make a downstream difference. (Unlike hiring committees, journal editorial decisions often do require unanimity for publication among the editorial board, since acceptance rates are kept low because journal pages are limited.) This discrimination is partly because of active anti-conservative bias, and partly because of other incentives. As one conservative academic recently recounted, he submitted a book proposal on conservative thought to a respected academic press only for that proposal to be rejected because it didn’t want to get a reputation as the kind of press that publishes more than a token handful of conservative books. That reputation would prevent it from attracting manuscripts from left-leaning authors, which all the stars in the field are. So conservatives are actively kept out of mainstream left-leaning journals and presses. Could conservatives just found their own journals? Eh. That takes a lot of time and money, and the journal would lose money because libraries wouldn’t pay to stock them. (Because no academics at the institution would request access from the library, because the established academics are all progressives with no interest in reading conservatives writing for other conservatives in the Journal of Conservatives.) The resulting journals would inevitably be considered “low quality,” of course, and thus publications in them would not really be useful in hiring decisions.

The second point is a concession. Yes, “moderate affirmative action” would not address the problem of anti-conservative bias, in publication or elsewhere, in light of all of the above. But that just means that moderate affirmative action is the least we could do in order to increase conservative representation in academia.

Yikes, this went on longer than I intended. Sorry. I’ll sum up the main points:

Hiring decisions are often inevitably made on more or less arbitrary grounds.

Moderate affirmative action is therefore not worse than other rationales for hiring on arbitrariness concerns, and can therefore be justified if other goods can be achieved through those means.

Affirmative action can remedy discrimination and increase diversity.

Intellectual diversity is good.

Conservatives have been discriminated against in academia, and remedying that is good.

So moderate affirmative action for conservatives in academia is justified.

I’m willing to defend all of this in print. Now the argument has been made, in as much detail as I can muster. It cannot be dismissed with a laugh anymore. Where does it go wrong?

I omitted a few sentences where Leiter says that the only defensible justification of affirmative action has nothing to do with “diversity” but with remedying past discrimination. More on that soon.

I found both of those charts in the piece by Jesse Singal I linked above. I’d been tinkering with this piece for a few weeks, hesitating to finish it in part because I didn’t want to take the time to find these studies and pull out the relevant tables. Thanks to Jesse for doing the work for me!

What about actual existing conservative politics would lead anyone to think there’s a bunch of interesting ideas we’re missing out on? And if you’re going to say that actual existing conservative politics aren’t what’s relevant, then you need to disambiguate what we mean by “conservative.”

I have defended views, in print, about the rationality of arbitrary decisions, and I want to chime in to day that the first premise is false, and your argument for it seriously flawed. Your claim that political viewpoint is as arbitrary a basis on which to make a hiring decision as teaching ability or research productivity is false, I think. The latter two qualities are directly related to the function of an academic, and it would be irrational to ignore either of these qualities in one's deliberations. It would *not* be irrational to ignore a candidate's political ideology, since: it is not directly relevant to the candidate's ability to carry out the function of the job, nor grounds the candidate's merit, but only serves as a fallible indicator of it, and a very poor one at that. It would be perfectly reasonable to exclude a candidate's political views from the discussion entirely when far more reliable indicators of merit are available, and that is often what rightfully happens. As you yourself recognize, the best case to be made for regarding a candidate's political views as a merit appeals to the beneficial social consequences for doing so. But the fact that no case of that sort need be made for publishing output or teaching ability starkly highlights the asymmetry between the traditional hiring criteria and the one you put forward. Perhaps, as you say, the weighting assigned to those uncontroversially relevant factors is idiosyncratic, but that doesn't make it rationally arbitrary, since these views are based on professional judgment, not coinflips. Even if we grant you that the weighting or these factors is arbitrary, it does not follow that the hiiring decisions which follow from them are arbitrary in any sense which detracts from its legitimacy. Yet your claim that arbitrary weighting of things that indisputably matter is as arbitrary as hiring on the basis of some factor irrelevant to a candidate's ability to perform the job's functions when you say that we might as well hire on the basis of political viewpoint. That's not defensible. You go on to conclude that we might as well hire on the basis of an arbitrary factor which has positive social consequences, if we're going to choose arbitrarily anyway. You may be right that we should use social consequences as a tie-breaker, but as I have just shown, political views are rationally ignored and irrelevant to merit, while hiring on the basis of teaching and research ability in some proportion has a clear warrant and rationale grounded in the functions of an academic.