The Trolley Problem

Understanding one of philosophy's most famous thought experiments

One of the most well-known philosophical thought experiments is the so-called “Trolley Problem.” There’s a well-known Trolley Problem meme, there was an episode of the philosophically-oriented sitcom The Good Place about it, and there were even a rash of articles published a few years ago about how the Trolley Problem is an important problem from the perspective of how to design self-driving cars. Yet this problem is widely misunderstood. Let’s clear up the confusion.

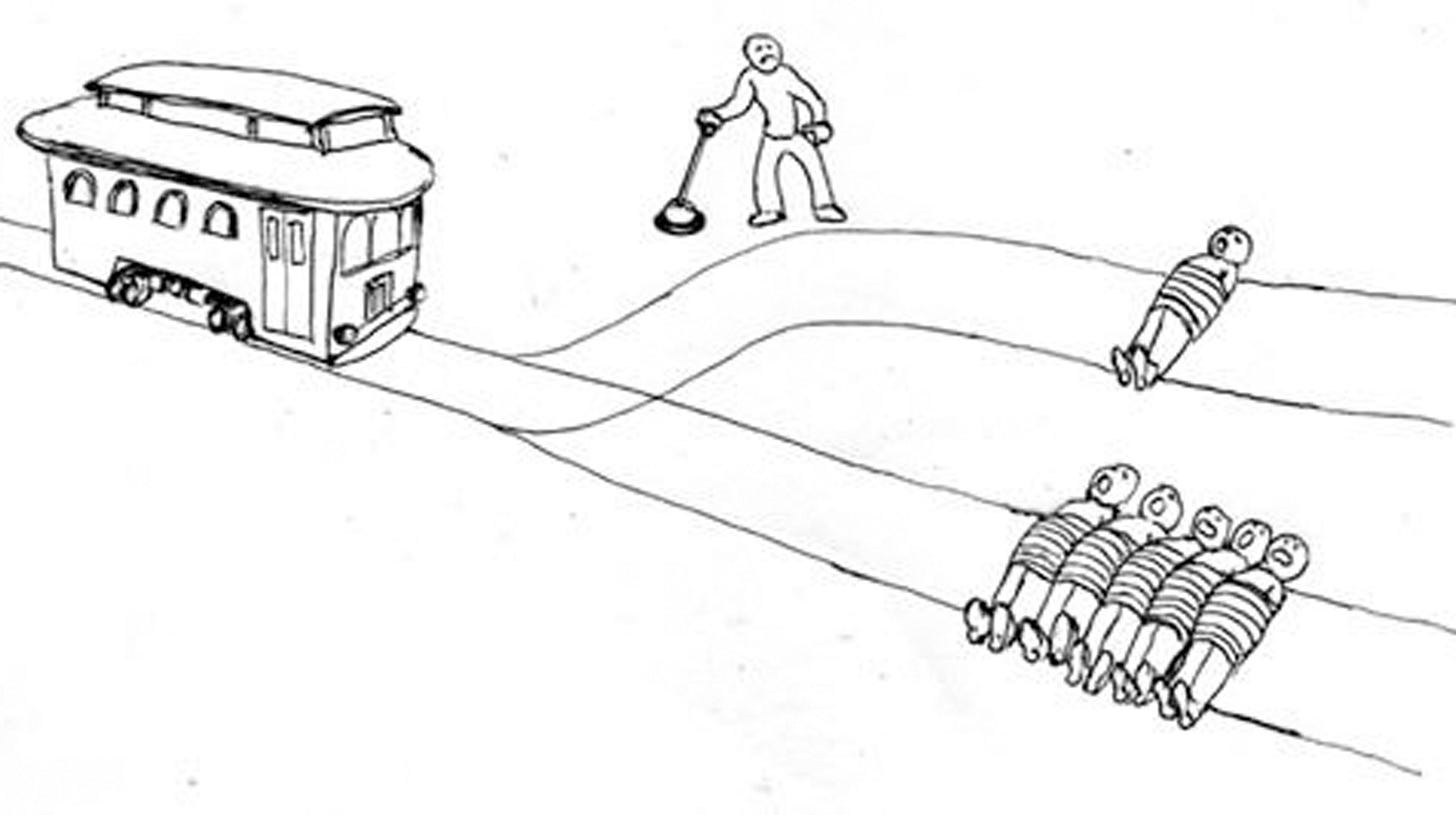

The core of the “Trolley Problem” is the following thought experiment:

A trolley is barreling out of control down the tracks. You can see it, but you can’t stop it. Down the line, you can see five people. They are on the tracks, but can’t get off; the embankments on either side are too steep (in some variants, the people are tied to the tracks). Next to you there is a switch. If you hit the switch, you can divert the trolley onto a side track, saving the five people. But there is one person on the side track. If you hit the switch, that person will be killed instead. What do you do?

Take a second; a think about it. What would you do if you were in that situation?

Got your answer yet? I’ll bet I know what it is. In fact, I’ll place that bet at 5:1 odds. I bet you’d pull the switch.

Why would I bet that you’d pull the switch? Because this is what everyone says. The practical problem — to pull the switch or not to pull the switch — is not particularly controversial. Now, of course, not everyone says they’d pull the switch. But there have been empirical studies, which are reasonably cross-culturally robust, to see how people will respond to that question. And by about 5 to 1, a large majority of people say they’d pull the switch. You kill the one to save the five. The practical problem, “would you pull the switch?”, is what is often called the “Trolley Problem.” But that’s not what the Trolley Problem is.

The Trolley Problem arises when you consider a similar case:

A trolley is barreling out of control down the tracks. You can see it, but you can’t stop it. Down the line, you can see five people. They are on the tracks, but can’t get off; the embankments on either side are too steep (in some variants, the people are tied to the tracks). You are standing on a bridge overlooking the trolley path. Next to you is an immensely fat man, who is leaning dangerously over the side of the bridge. You could easily give him a shove, pushing him down in front of the trolley. He’d surely die from the impact with the trolley, but his immense girth would cause the trolley to slow or derail, saving the five down the line. Do you push the fat man?

Take a second to think what you’d do in this case. Here, again, I think I know what your answer would be, although I’d only bet on it at 2:1 odds. You would not push the fat man.

But why not? Both cases are identical in their essential moral choice. In both cases, you kill one in order to save five. Yet in the first case, the vast majority of people choose to kill one to save five, and in the second case, they don’t. What explains the difference? That’s the Trolley Problem.

Why do we care? For two reasons. First, it’s kind of a neat puzzle in human moral psychology. People clearly do treat these two cases differently, so something in our brains causes those cases to be processed differently. What is it? Figuring that out will be useful in uncovering the structure of human moral cognition.

But more importantly than this, it is widely assumed by those working in ethics that our intuitions about cases are a fairly reliable guide to moral truth. In the first case, you really ought to pull the switch, while in the second case, you really shouldn’t push the fat man. Figuring out the crucial difference between these two cases is therefore not just a matter of figuring out how human moral cognition works. It’s also a way of solving an important puzzle in moral theory, the puzzle of how bad consequences that we cause balance against bad consequences that we merely allow. After all, few of our actions that would seem to make things better are truly costless. Is it worth imposing costs on others to make things better; or not? Surely the right answer to that question is “Sometimes it is, and sometimes it’s not.” But when is it, and when is it not? Figuring out the difference between the two cases in the Trolley Problem looks like it could be the key to answering that question.

Unfortunately, although there are lots of similarities between the two cases, there are also lots of little differences that might be relevant to why we treat these two cases differently. So for a while around the 1990s, there was a huge surge in interest in what came to be known as “Trolleyology,” where philosophers proposed a dizzying array of variations on the trolley cases in order to try to identify the one factor that causes our intuitions to flip from “kill the one to save the five” to “don’t do that.” What if the man on the bridge is not fat but is just wearing an absurdly heavy backpack? What if the person on the side track is so fat that their body will stop the train? What if the side track meets back up with the main track so that the five will only be saved if the one person is fat enough (or has a big enough backpack) to stop the trolley? And so on, and so on, for hundreds of papers published in ethics journals.

Eventually, the fad died out. For one thing, as the cases got more and more complicated, people’s intuitions became less and less certain, and philosophers started to doubt that they were really making any progress. For another thing, it started to seem increasingly absurd that we could figure out the nature of our obligations to one another by examining increasingly-complex diagrams of trolley tracks. So, for the most part, philosophers moved on to other, less embarrassing issues.

But the fact is that the Trolley Problem is not the practical problem of whether you should pull the switch, killing the one to save the five. So all of those articles about the Trolley Problem and self-driving cars are profoundly stupid. The premise of all of those articles is the same: When we’re programming self-driving cars, we need to decide what to do, in advance, if the car encounters some problem. So what if there are people in the road, and the car needs to decide which group of people to hit!? This is a puzzle we need to solve now, in our programming of these cars. And an old puzzle from moral philosophy might just be the key to solving the problem.

This is a stupid premise for two reasons. First, engineers designing self-driving cars face a practical problem of what to do. The Trolley Problem is not a practical problem. So there’s really no relationship between the two problems. Second, cars aren’t out-of-control trolleys! Cars don’t run on tracks. They have unlimited freedom to swerve and turn in a direction where there are no people. But, more importantly, self-driving cars can just hit the brakes, in a way that you can’t in the Trolley Problem cases.

So the practical problem for the engineers is really quite easy: When there are people in the road, just hit the brakes. What if the brakes are out? That’s unlikely, but ok, if the brakes are out, swerve to avoid people. What if the brakes are out and the steering is out too, except the car can only swerve a little bit into one predetermined trajectory, and there’s one person on that trajectory, but if the car doesn’t swerve it’ll hit five people? How would you program a car to deal with that situation? And the answer is you don’t program the car in any way to deal with that situation because that will never happen. You’re just asking the question in order to show off your misunderstanding of the Trolley Problem case you heard about in your undergraduate ethics course. So hey, good for you, you got a B- in Intro Ethics. That has nothing to do with how to design self-driving cars.

In fact, “just hit the brakes” is such an obviously correct solution to the problem that the real problem for self-driving car fleets is that they cause massive traffic jams. “When in doubt, hit the brakes” is a good rule for safety, but if you’ve got multiple self-driving cars in doubt in the same intersection, they sit there blocking traffic forever until someone can be sent out to manually maneuver them out of trouble. That is a real engineering problem for designing self-driving cars, but it’s kind of the opposite of the Trolley Problem.

Now you know what the Trolley Problem is all about. Let us never speak of it again. It’s pretty dumb.